Some Thoughts on Mixed Ability vs Setting

In the last week alone, I have heard an Ofsted inspector call for maths teachers to move to mixed ability teaching and an apparent ‘official’ government body insist that all pupils within a year group should always be learning the same mathematical concepts.

This has been pretty much a weekly occurrence now for the last year or so.

The explanation must be, of course, the striking new evidence that mixed ability teaching in mathematics is more impactful than teaching maths classes in sets, where learning content is targeted at the point in the journey through mathematics that each set has reached, right? There could be no other logical or defensible reason for such influential bodies to call on schools across the country to undertake such a huge change in their pedagogy, curriculum planning, teaching methods, staffing, timetabling, resourcing or fundamental beliefs, right?

This new evidence, which puts the nail in the coffin of the old setting vs mixed ability debate, must be so overwhelming, so robust and trialed that we should all fall in line with the calls from these official bodies, right?

The trouble is, there is no new evidence. Nothing at all. Nothing to suggest an urgent and state mandated response to hurry schools up and down the land to swap to mixed ability teaching. Zero.

Well, that’s kind of odd. Why would Ofsted and a Maths Hub be calling for this approach if there is no evidence to support such a call?

A brief discussion on mixed ability vs mixed attainment vs setting

It is central to the idea of a mastery model of schooling that time is the key variable and that all pupils are able to move through the learning of a discipline at pace because they are working at the right level of demand. An implication of the mastery cycle – with its aim of ensuring every pupil grips every idea through careful instruction, diagnostics and responsive correctives – is that the groups do indeed become highly homogenised. The implementation of the mastery model from the very start of schooling removes the need to debate how to react when attainment gaps are large – they have been removed by design.

However, given that many readers of this blog will not be in a position to implement approaches from day one, it is worth taking a moment to pause and consider why the arguments around the grouping of pupils are so fierce and what the implications might be.

The discussion around how to group children when learning mathematics is as old as maths teaching itself. It is quite right that we should ask which is more impactful. Numerous studies and meta-studies have looked at the question and there is a wealth of published research on the issue. What does it find? Well, broadly, that there is little difference in outcome. Some studies suggest a slight improvement for low-ability pupils in mixed-ability groups; some suggest high-ability pupils achieving worse results. Some suggest high-ability pupils doing better in setting, with low-ability pupils doing worse. Some highlight the common practice of ‘teaching to the middle’ in mixed-ability classes. Some studies show no impact at all. It is fair to say the broad picture of evidence in the debate is really rather fuzzy and the evidence certainly weak.

The main weaknesses in the data come from the tendency of studies in this area to conflate very different issues. Most studies looking at ability grouping combine the practice of setting with other, non-analogous, practices such as streaming and other groupings. Prima facie it is clear that setting and streaming are in no way relatable for the purposes of a robust study. The second weakness is the common practice of carrying out these studies without considering the subject-specific nature of pedagogy, didactics and hierarchy. Studies tend to look at pupils across many subject areas, rather than commenting on the differences within studies. Where studies have gone further – for example, Ireson and Hallam (2001), which looked at mathematics separately – the results are often quite different (in this particular case, showing setting improves outcomes in mathematics slightly).

For the moment, the evidence remains pretty much as it has been for a couple of decades: mixed and unreliable.

So, why change?

In England, from the point of coming to power in 1997, the Labour government repeatedly published commentary stating that schools should set children by ability unless there were extraordinary circumstances to justify mixed-ability teaching. So strong was the belief in the efficacy of setting, both in terms of attainment and social justice, that Labour asked the school inspectorate, Ofsted, to penalise schools where mixed-ability practices were deployed.

The government published statements making clear their belief that mixed-ability teaching can work, but only in cases where the teachers delivering were exceptionally good at doing so. For over a decade, the government maintained its view and made clear its beliefs to all schools. It is no surprise, then, that the majority of maths lessons in England’s secondary schools occur in setted classes. As a result, most maths teachers have learned their craft in teaching mathematics in non-mixed-ability classes. The workforce is set up to teach groups of children set by ability.

Given there is no new evidence to suggest a system shift towards mixed-ability teaching, it is curious that the notion is gaining traction. It is even more curious that some proponents of mixed-ability teaching are including in their justification for doing so a description of a mastery approach, failing to mention that all successful implementations of a mastery model of schooling have included grouping pupils based on their current level of attainment. In many examples, such as those that Washburne and Bloom worked with, this included further steps to even more closely homogenise groups by operating non-grade settings. In non-grade settings, pupils can be set across age groups, giving schools even more scope for creating groups with narrower attainment gaps. Many jurisdictions, today and historically, have achieved these elements of non-grade settings by not allowing pupils to graduate from one year group or grade to the next unless they can demonstrate they have fully gripped the necessary ideas to make such a step up successful.

Throughout my career as a maths teacher, I taught some classes that were setted by attainment and some classes that were so-called mixed ability. I loved every minute of it. It was by pure luck that the first school I landed in as a trainee teacher was a utopian, hippy kind of place. The maths department (by far the best maths department I have ever known) was staffed by huge intellects, all of whom were over the age of 50. Their combined knowledge on the teaching process was immense. Classes were truly mixed, which meant I had to learn how to deliver mathematics lessons with the lowest-attaining and highest-attaining, lowest-ability and highest-ability pupils all in one room. It was a blast. The intellectual challenge was huge and I relished it. Every member of the maths team truly believed in mixed-ability classes and had become masterful in their practices and pedagogies specific to mixed-ability teaching to ensure they had high impact. Those are the pedagogies and practices I developed too and I remain thankful for that.

The Labour government’s claim that mixed ability is only impactful with very specific types of teachers resonates with me. I have watched so many teachers being forced to teach mixed-ability classes without having had suitable professional development and time to develop necessary practices, and it has always resulted in sub-optimal lessons. Often a complete waste of time for everyone involved. As a young teacher, this used to upset me greatly, wondering why the outcome was so bad. Of course, as one learns more about teaching, one comes to realise that shoehorning a teacher into a pedagogy is always a disaster.

Social justice

An oft-wielded argument in support of mixed-ability teaching is the ‘education for social justice’ angle. I loved that my mixed classes were not segregated, loved that my pupils had equality of opportunity, loved the social interactions and what, as a young teacher, I believed to be the removal of stigma. But the social justice argument just doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Real social justice comes from becoming learn'd, from becoming autonomous and being able to lead a purposeful and meaningful adult life.

Yet, the evidence tells us that mixed-ability practices don’t result in greater gains in terms of achievement at the end of schooling.

But what about those pupils who would be placed in bottom sets? Surely they feel more included and less stigmatised? Yes, some do. But, also, some don’t. Where mixed-ability teaching is forced upon teachers who have not developed necessary practices, the tendency to ‘teach to the middle’ leaves the lowest-attaining and lowest-ability pupils adrift, alienated and, most importantly, unable to learn. This returns us to the Labour government argument of mixed-ability teaching only being defensible with appropriately skilled teachers.

And what about the highest-ability pupils? Clearly, ‘teaching to the middle’ fails them. But, I have seen many mixed-ability classes where high-ability pupils are stretched and challenged because the teacher has sufficient subject knowledge and developed pedagogies to enable them to take a mathematical concept further and deeper than the aspirations of the national curriculum. This is wonderful to watch. Sadly, this is not common practice for two reasons. Firstly, most teachers have been trained to teach in a setted situation, where it would appear on first look that the content can be constrained to a fairly narrow inspection (more on that fallacy later). Secondly, the subject knowledge of teachers is not always sufficient to understand how to stretch a concept. This latter point is driving some of the worst practice I have witnessed in England’s schools, which is also a result of official bodies erroneously spreading the myth that all pupils should learn the same content, namely the practice of keeping high-ability pupils on mundane work for months on end. An increasing number of teachers and parents are telling me about their frustration at this practice, with many going further to say that officials have told them they are ‘not allowed’ to let the pupils progress further up the curriculum no matter how secure they are in the concepts they are being kept on. We do, of course, want to give pupils as many opportunities as possible to behave mathematically, so once an idea has been gripped, it is desirable to give the pupil opportunities to explore the concept further and more deeply, making connections and solving problems. But there is a point where pupils should move on. The idea that all pupils should be kept on a concept arbitrarily is simply wrong.

So, the social justice argument doesn’t appear to be the driver either. After all, the Labour government was very committed to education for social justice too.

Ability or attainment

There is a current movement arguing that the term ‘ability’ is damaging and should be replaced instead with ‘attainment’.

There is a slight problem with this argument: as discussed earlier, the words don’t mean the same thing.

Emotive language is used to try to advance this mind-numbing claim, with some people asserting that the word ‘ability’ is ‘dangerous’.

This attempt to redefine language is a common tactic when trying to create a deliberate dark age and gain control for ideological reasons.

The greatest problem with the mixed ability vs setting debate is the fanatical tribalism of those at the extremes of both sides (sides that the evidence suggests there isn’t a modicum of difference between). Trying to discuss mixed ability or setting is often difficult because the debate is shut down by no-platformers, who will not accept any challenge to their beliefs, no matter how unsupported by evidence they are. Using words like ‘dangerous’ is a way of shutting down debate. Who would want to be a ‘danger’ to children?

Ability is not a dangerous word; it is a very helpful one. As is attainment. The difference between these words, in an education discussion, is really important and formative.

Attainment is the point that a pupil has reached in learning a discipline. It can change; pupils can unlearn as well as learn. It is not precise. But it is very useful in determining appropriate points on a curriculum from which to springboard pupils to new learning. We, as educators, continually assess these attainment points so as best to ensure the curriculum we are following can adapt and flex to what has been understood or forgotten. Knowing the prior attainment of pupils (rather than what has been previously presented at them) is crucial if we are to ensure pupils are learning appropriate new ideas and concepts.

Ability is an index of learning rate. It is the readiness and speed at which a pupil can grip a new idea. It can change; as with all human beings, pupils will make meaning from some metaphors, models or examples, more readily than they will of others. In maths, for example, we often see pupils quickly understanding some numerical pattern, say, who then take a long time to grip a geometrical relationship. An individual can have a high index of learning rate during some periods of their life and a low one at others. Again, as educators, we are continually assessing ability so that we are able to best judge the amount of time, additional practice, new explanations or support that a pupil needs in order to really grip an idea. Knowing the ability of a pupil (rather than woolly ideas of engagement or enjoyment) is crucial is we are to ensure that pupils are learning new ideas and concepts for the appropriate amount of time (rather than some arbitrary amount of time presented on a scheme of work).

Current attempts to abolish the word ‘ability’ from education’s lexicon are deliberate in trying to remove nuance from the debate. The fanatics do not like nuance.

All classes are mixed attainment and mixed ability

One issue with the practice of setting pupils is the assumption that those setted classes are now homogenous. They are, of course, not. Setting is merely a way of narrowing the attainment range within a class. With a narrower attainment range, teachers may focus their attention on fewer aspects of a concept and spend a greater amount of time with a greater number of pupils on the crux of the matter. The class will still contain pupils who need to access the concept at a lower entry point and those who have already gripped the focus of the lesson and can be stretched further in their thinking. The teacher must still be aware of the prerequisites and the possible areas for extension. The narrowing of the attainment range is a mechanistic way of maximising teacher focus. The range of abilities in the class is also always present in setted classes. Pupils will grip ideas at different speeds through different metaphors and explanations. This is true of the highest attaining and of the lowest. A common misconception is that pupils in low sets have very similar indices of learning rate. They don’t. There will still be pupils who grip ideas very quickly because the ideas are being pitched at the right level for the pupils and the examples or models have resonated. Similarly, there will be very high-attaining pupils in the top set who take a long time to grip an idea because the way in which it has been communicated has not allowed them to make connections to already known facts and ideas. The teacher must be aware of these attainment and ability ranges when working with pupils arranged in sets. The effective mixed-ability teacher appears to be more alert to these differences; the ineffective mixed-ability teacher ignores them and teaches to the middle. There are pros and cons in both approaches.

The impact of attainment range

Advocates of mixed-ability teaching will often argue that the attainment gap does not matter – it can be any size. This is easy to dismantle reductio ad absurdum: would one advocate a class containing an individual who cannot number bond to ten and another who is red hot at advanced Fourier Analysis? Of course not, so there is a range where the defence falls apart. The debate is really about how wide that gap can be and still maintain efficacy with a highly expert teacher. Those who refuse to engage with the nuance of the debate, choosing instead to maintain a fanatical stance of insisting the range can be of any size, serve only to weaken the argument for mixed-ability teaching. I see many schools addressing the issue through logistical solutions such as having a top set and bottom set, but then six mixed-ability classes between. This hybrid approach is a way of taking some account of the normal distribution nature of a year group. I would welcome research on these hybrid approaches so the impact can be better understood.

How big can the range be? This is really the question. We know that all classes are actually mixed attainment and ability, and that setting is simply a way of reducing the attainment spread to bring about efficiencies for teaching. The typical attainment range in mathematics at aged 11 in England is seven years of learning. Every secondary teacher knows this; we all know 11-year-olds who can so some pretty sophisticated mathematics and some who can’t year count to ten reliably. Should these pupils be in the same class? Should these pupils be forced to be in the same class with a teacher who does not subscribe to the approach and has not been trained to be impactful in such a setting? Is it possible to be impactful across all pupils when the attainment range is seven years? These are the questions schools need to ask.

Thinking of changing?

The outcomes in both mixed ability and setting can be great. The outcomes in both can be awful. It is the practices, structures, logistics and pedagogies that bring about efficacy or not. But do not for one minute believe there is any requirement upon you and your school to change. There isn’t. The national curriculum is quite clear in its aspiration that the majority of pupils should learn the same content. Of course they should. The population of pupils is a normal distribution, so the majority around the mean are broadly similar in both attainment and ability. But majority simply means any number larger than 50%. Not all. There are many, many pupils who should be learning different materials, either because they are not yet equipped to learn the material of the majority or have far surpassed the majority.

I really loved teaching mixed classes. But I have a pedagogy and you have a pedagogy and they are not the same and they do not have to be the same. If, as a whole maths department, you decide you want to teach your classes in sets, do. If, as a whole maths department, you decide you want to teach your classes in mixed-ability groups, do. But, with either of these decisions, it is crucial that you understand and take seriously the huge burden of professional learning that must come first. Just like moving your model of schooling from conveyor belt to mastery, moving from setting to mixed or mixed to setting takes years of careful planning, dedicated professional development, resourcing, profound changes to pedagogy and an adherence to the principles of making the model work effectively. Sadly, I increasingly come across schools where a grand pronouncement has been made – ‘From September we will move to mixed-ability classes’ – without a single thought for the consequences. A school making such a significant change to their model of schooling without the required focus and effort of the years of professional development it takes to transition successfully is simply setting teachers and children up to fail. When I meet headteachers who tell me they are changing to mixed ability at the start of the new school year, I always respond, ‘Wow, that’s amazing. The commitment and forethought you must have given this five or six years ago and the funding you must have invested in all of your staff over those years to develop their pedagogical approaches sufficiently is really commendable. Can you tell me about it?’ Those headteachers who look at me sheepishly and reply ‘We took the decision last week and will have a few days professional development in the summer’ really have no right to be leading a school.

Parental views and better evidence

The evidence in support of setting or mixed is highly varied, highly unreliable and tells us nothing of value. For every report supporting setting, another supports mixed. The methodology behind the research is very often designed to find precisely the outcome that the researcher or the funder of the research wished to find. The argument around how to group children is so fiercely driven by deeply held ideologies that it is almost impossible to unpick anything useful from the research.

The ideological beliefs surrounding the grouping of children are also strong in the population of parents. It is important for schools to understand the position that the parent body holds if they are to transition smoothly from one model to the other.

Schools can survey parents and prospective parents to garner their opinion.

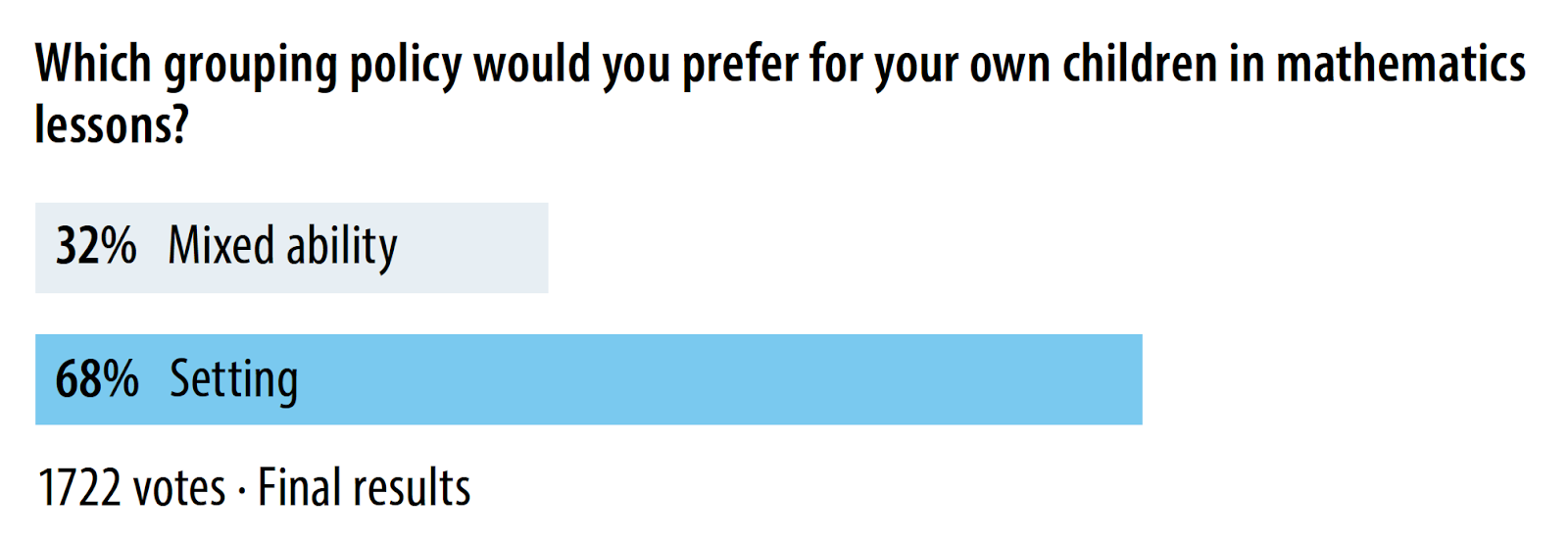

As a quick litmus test, I posted two polls on Twitter. Clearly, such polls do not stand up to rigour since no attempt is made to stratify the sample or account for social media presence and following. However, the sample size is large enough to at least begin a discussion.

When given only the option of mixed ability versus setting, a significant minority of parents voted for mixed.

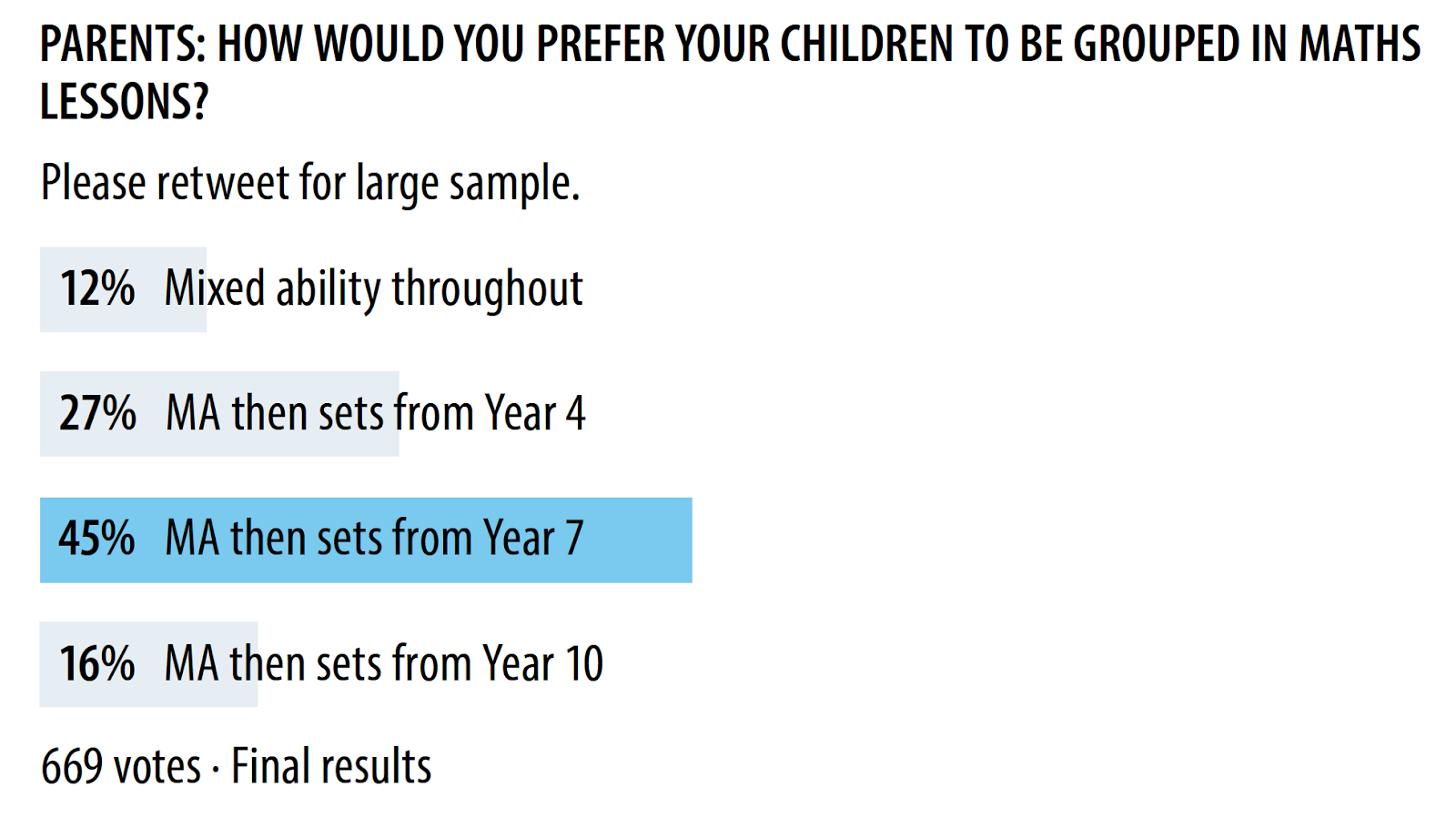

But when given a slightly more nuanced choice, support for a completely mixed-ability approach plummets. There appears to be a strong belief that there is a right time for pupils to be set in mathematics lessons. This is certainly the feedback I have received from parents over the years too.

The debate around how to group pupils will, undoubtedly, continue for many years to come (and perhaps will never be resolved), particularly while the research into the issue remains so unreliable.

I have a set of tests that I believe a study into mixed ability vs setting should be required to pass before it can be considered credible:

- The study must not conflate grouping types. Setting, streaming, banding, in-class grouping, etc. cannot be treated as a single case.

- The study must be subject specific. Hierarchical subjects and non-hierarchical subjects cannot be measured together. Individual subjects must be investigated separately.

- The study must take account of teacher quality. A study that claims to find impact of mixed ability or setting by treating such impact as univariate is of no value. The issue of pupil outcomes is complex and the study must be multivariate.

- The study methodology must be designed by a disinterested party. A proclivity towards either mixed ability or setting biases methodology design.

- The study must be funded by a disinterested party.

- The study must stratify results on the basis of the attainment gap that exists in the observed cases and look at variance in outcomes.

- The study must include analyses of teacher demographics in the case study institution, particularly experience level of subject management.

- The study must report on prior grouping practices encountered by the pupils and timeframes in shifting to the current model.

- The study must report on length of experience case study teachers have in teaching particular grouping types.

Research into this issue has not yet met these tests. Studies almost always conflate grouping types and combine results from different subject areas. Crucially, studies have not taken any account of teacher quality, which I view as the single most important variable at play here. Researchers often object that designing studies that address the issue of teacher quality is too difficult to achieve, particularly given the challenges of generalisabilty from small-scale experimental design. But, without addressing this issue, the claims made by such studies are farcical. A complex, univariate issue cannot be distilled to a simple sound bite focused on one variable.

In discussion about this issue, Dylan Wiliam commented: ‘I actually think that it is difficult to overplay the issue of teacher quality, since the impact of teacher quality is likely to be an order of magnitude greater than the effects of ability grouping policies.’

I hope that the research community will, at some point in the future, be able to provide the teaching profession with better-informed, multivariate analyses on the issue of how to group pupils for the greatest gains. Until then, schools should ensure any move they choose to make reflects the requirements of the families they serve and is supported thoroughly with pre-emptive, significant professional development over a substantial time period for all teachers who will be involved in the change.

From the perspective of a mastery approach, which I advocate, the issue of grouping fades away. When a mastery approach is adopted and fully embedded from the very start of schooling, the diagnostic and responsive cycle of the mastery model results in groups of children becoming highly homogenised, with the teacher ensuring that no child is left behind. This homogenisation of pupils ensures, with expert teaching, that all classes can move through the learning of a discipline at pace and with success. This success drives motivation and the cycle becomes virtuous.

For schools considering the move towards a mastery model of schooling with older pupils, it is a case of carefully working out the broad starting points of each pupil in the cohort and then grouping the pupils such that the attainment gap is not too great. These groups can then be treated as normal in the mastery cycle, but with the teacher ever mindful that pupils’ ability and attainment is not fixed and may require the fluid movement of pupils between groups.